Professor Wagner: With Gülen, the key is love

Date posted: November 5, 2013

AYDOĞAN VATANDAŞ, NEW YORK

In his recent book, “Beginnings and Endings — Fethullah Gülen’s Vision for Today’s World,” Professor Walter Wagner shares his insights about Gülen’s take on Islamic eschatology and the challenges of the contemporary word. According to the Wagner, the world is faced with a leadership crisis whose resolution could fulfill the prophetic message of love to human beings. In the last century, the world suffered under authoritarian leaders who were unable to meet the needs of the people.

Wagner says: “There was a Hitler, there was a Stalin, and there was an Osama bin Laden. We must be very careful and we must examine the heart. In Gülen’s case, the key is love. If the charismatic leader does not lead you to love, does not lead you to acceptance, you should be careful. We live in a world where people are hungry for leadership and, in this country, hungry for leadership and the end of stalemates. We need to say we need leadership. Some of that will be God-given, but also cultivated. [It is] cultivated in the mosques, in the schools, in the churches and synagogues, and it means not fearing the other person. That’s key. Gülen is not afraid.”

Today’s Zaman interviewed Wagner about his recent book and his insights about Fethullah Gülen.

How did the idea to write a book about Mr. Gülen arise?

I have a number of students at the Moravian Theological Seminary at Bethlehem. I also teach at the Lutheran Centre. I am a Christian, I’m a Lutheran-style Protestant Christian and I have a number of Turkish Muslim students who are members of Hizmet, are inspired by Hocaefendi Fethullah Gülen. I also had the honor — I don’t know if that’s right [to say that I had dinner with Mr. Gülen] — to even have dinner, once, with him and with several others and I was very impressed by the spirituality and the depth of the man. He does have an atmosphere about him, [a] very gentle atmosphere, but yet deep. This became quite clear. And along with that, I became interested in him. [My] book on the Quran [“Opening the Qu’ran: Introducing Islam’s Holy Book”] was written before I had any contact with Hizmet or before I had contact with any Turkish community. I had been to Turkey once on a tour as a result of iftar dinners. There was a conference at Temple University, in Philadelphia, at that conference someone asked me if I’d like to present a paper. Academic 15 minutes of fame; actually it was squished down to 12 minutes since I was the last one and told, “Hurry up, because there’s another use for this room.” It was a conference on Fethullah Gülen and his views and influence on peace, environment and the Creation. I began to think, “How could I do something?” It occurred to me that the heart of his theology and his spirituality and of the movement is in the creation of the world, the creation of human beings and the destiny of human beings and the afterlife with, “What do you do in between?” Your beginning and resurrection. It seems to me, reading him and the reading of Said Nursi, that that was the key to his thought, but in looking at the literature and in looking at what others have said, they spoke more of him and of Nursi and of Hizmet as social movements, of changing the society, dealing with curriculum and so on. And I thought, you have to see the larger picture of where this life begin, what it is all about and where it’s going and then — also it was part of the study of the Quran that I had these materials — it became helpful to, then, look at that and to be helped by the students.

Eschatology-related issues at center

So, you primarily focused on his vision and thoughts about the beginning of the worlds and his vision about eschatology. This is why eschatology-related issues are very central in your book. Is that correct?

Yes, especially about before the absolute end. There are two ways of looking at end, one is cut off, another one is fulfillment — this is also Biblical, both are in the Bible, both are in Christianity and in Judaism — and he looks for the fulfillment of this world with a role of Jesus/Isa, peace be upon him. … You don’t have to run directly to chopping off the world. … God gives us the opportunities to fulfill God’s plan in this world now. That’s one of the ideas to fight ignorance, poverty and division. It fits with the plan of Hizmet.

Is there anything you’d like to share with us about your impressions from when you talked to him?

In the conversation with him, the deep respect that he engenders. For those who know him, he is the kind of person [that] when he comes into a room [people stand up], not just because the students … or the people I was with know him. … He’s a man whose presence makes you want to stand up, out of respect for him, out of honoring him. He was able in the conversation to draw people out. He does not speak English, so we had a translator. How he engaged everyone around the table, very quietly but very insightfully, taking a person’s comment or question and making more of it than the question asker ever thought would be there and engaging with [it]. When someone said something, Hocaefendi would say, “Well, think of it this way.” He is a good teacher.

Tell us a little bit about your methodology. What kind of research did you do, what kind of books did you read to write this book?

Part of my own academic preparation, my field is early Christian history and the whole … of Christian history, as well as Biblical material. So I was familiar with eschatology. I have taught courses on the testaments and in those areas. I knew a little something about Islam. I grew to know more about it. Part of the methodology, as you ask, was in the research. I was, actually, working on another book, which is still in a box in my study. When they suggested, “Why don’t you go ahead and take the paper that you gave at Temple, flesh it out and go with it?”

Let’s talk a little bit about the similarities and differences between the perceptions of eschatology in these three religions. Do you think that eschatology is as central to Islam as it is to Christianity?

I think so but the term is not used in Islam. End times, resurrection may be more terms that are used but I think the concept is present. In Judaism it’s very much mixed, as it would be biblically, in what the Christians would call the Old Testament. Sometimes many Jews would say, “We’ll leave that to people who speculate, to people who want to set up calendars.” That’s very dangerous; there are Muslims who want to set up calendars as well. Muslim apocalyptic thinking, end-of-the-world kind of thinking. Most Jews will say, “Let God take care of it. We’ll work as hard as we can with justice, compassion.”

[In] Christianity, this is very different. Christianity grows out of Judaism as a movement within Judaism that stressed the coming of the Kingdom of God, and the question was, “When is it coming?’ Some looked at it as end, some looked at it as fulfillment, and biblically, in Christianity, those two ideas go side by side. There is a concept among some Christians, which will have Jesus influencing the world from a heavenly place or another dimension … and inspiring persons to live as best as they can, in mercy, compassion, service, humility, not giving into the affairs of society, the morality of society. That passes into Islam and that was one of the things I saw in Hocaefendi. Where Jesus does not have to return physically but can be an influence on persons who are attuned, whether they are Muslim, Christian or Jewish or they don’t know what they are yet.

Gülen at the center of Islamic thought

When you focused on Mr. Gülen’s opinions about eschatology, what is your take on that?

I think what he’s adding to, what he’s doing with this — he is creatively taking the material from the Quran, from Hadiths materials and from Said Nursi, for example, and he’s creatively combining these, seeing how these ideas have developed, with an Islamic center to it. He is in the center of Islamic thought; he’s not off on any edge for he has his own voice; he’s not copying anyone, in a sense, just bringing it all together, hanging it all together. But rather, he has added the dimension that we need to understand a way in which to do things which aim at justice and aim at lifting people out of despair into hope. On that basis, there’s something distinct for him to see: That, as some of you are aware, the three great problems are ignorance, poverty and division. They ought to be addressed through education, social justice, lifting people up and dialogue. I think, and I’m trying to make a point, that it is very important that in interreligious dialogue — we do that in our area, we have 10 or 12 sessions, we’ll bring Muslims and Christians to address more spiritual issues — we need to address the issue of eschatology, that is yet to be addressed in the dialogues. We can talk about the Quran, we can talk about scripture, we can talk about prophecy, spirituality, family, women’s relationships and what they do with the kids. But to get to the deeper levels, we have to talk about what is life about. Where is it going and how we’re going to get there.

Islam is identified with violence and terror due to the wrongdoings of some groups or people in the Muslim world. How do you think Mr. Gülen has distanced himself from this and managed to promote exactly the opposite? What is his difference? How do you think he managed to do that and what was his motivation?

I think he’s been very clear, he has written about that. … He was very clear: “You cannot be a Muslim and a terrorist.” I think that was the name of one of his articles. It took a full page in the New York Times. No one was listening. The noise of 9/11 was too great for other voices to be heard. .. The Islamic Republic of Iran, for example, was one of the first to speak against that, as were many other Muslim groups. I think what he has done; he has certainly and consistently said that a Muslim cannot do it. The Quran forbids it. That this is a disaster that has been perpetrated in the name of Islam, and I think he has shown passages of the Quran. I think the movement, Hizmet, is emphasizing the role of dialogue and cooperation and to find the spiritual grounds rather than the political grounds for cooperation. It’s easy to talk about that we shouldn’t destroy each other, let’s maybe have tea together. That’s ok, that’s dialogue by tea and baklava but you need kebabs, you need to go deeper than that. He’s distancing himself, I think, through organizations that are taking shape in these Peace Islands Institutes. To create these islands of peace that can, then, grow into continents, as well as I understand some of that. To say that there is, also, an Islamic understanding of exertion for justice, for understanding, for education and for helping. The founding of schools and universities in Central Asia is highly important. What kind of Islam will come into Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan and the old Soviet Republics?

Some believe that interfaith dialogue is actually impossible. What’s your response to that?

Religions don’t dialogue, people do. That would be very important. People need to come together. They need to have baklava. They need to have whole meals together, to sit and talk with each other. I think through the students here present, that there is the hope, the expectation. Also, for characters of my age, I’m further down the chronological path than most people here, we must leave a better world behind us and we can do it! What Gülen has done is to really say, we have the ability to do it, get busy doing it. I’m not quite clear about the relationships of the Turkish movements and the other movements in the Muslim world, the connections.

I think you can point to people like Mahatma Gandhi, Archbishop Romero in El Salvador, young John Sobrino and others who are this way. There’s some kind of spiritual gift that these persons are given by God. We’d call this in Christianity a charisma, a gift that comes from outside. These persons can be inspired. They have a kind of magnetism to themselves, as well as a kind of sharing that will engender cooperation from others so that they’ll be, I don’t want to use the word infected. They’ll transmit this kind [of gift]. I think Prophet Muhammad, Jesus and others have this gift. They can bring people together and then send them out as well. This takes what can be called, biblically and also Islamically, the Wisdom of God. That’s one of the beautiful names of God in Islam. Also, very important is that such individuals walk the straight path. To go in the straight way that has been lined up. There can be people who have magnetism about them and send people out for destructive purposes, as well. I’m a German immigrant, old enough. There was a Hitler, there was a Stalin, and there was an Osama Bin Laden. We must be very careful and we must examine the heart. In Gülen’s case, the key is love. If the charismatic leader does not lead you to love, does not lead you to acceptance, you should be careful. We live in a world where people are hungry for leadership and, in this country, hungry for leadership and the end of stalemates. We need to say we need leadership. Some of that will be God-given, but also cultivated. Cultivated in the mosques, in the schools, in the churches and synagogues, and it means not fearing the other person. That’s key. Gülen is not afraid.

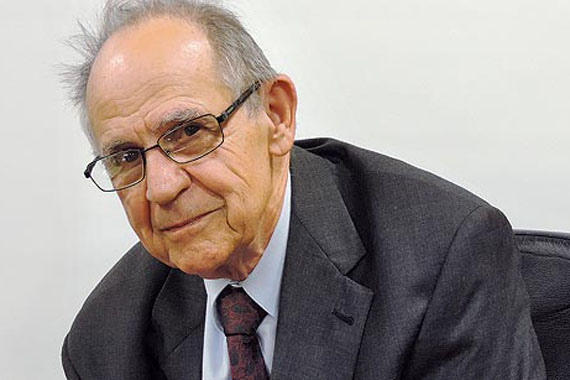

Profile:

Professor Walter Wagner is adjunct professor of history and Islamic studies at Moravian Theological Seminary. He is the author of a number of books, including “Opening the Qur’an: Introducing Islam’s Holy Book” and “After the Apostles: Christianity in the Second Century.”

Source: Today's Zaman , November 5, 2013

Tags: Book reviews | Fethullah Gulen | North America | USA |