Turkey Assails a Revered Islamic Moderate

Date posted: January 1, 2012

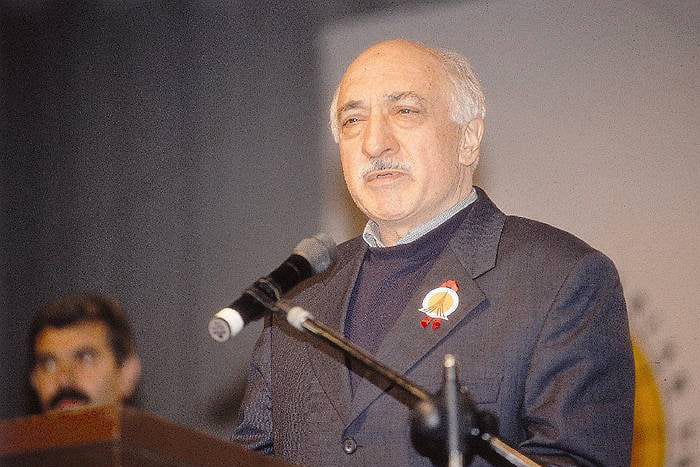

Though little known in the United States, for many years Mr. Gulen was an unofficial ambassador for Turkey who promoted a moderate brand of Islam. He preached tolerance, meeting with Pope John Paul II and other religious and political leaders, among them Turkey’s prime ministers and presidents.

DOUGLAS FRANTZ, August 25, 2000

Onur Elgin, a Turkish teenager, has no doubts about why he spent his summer vacation studying physics. In fluent English, he explains that he wants to succeed for his school, his country and the world.

Onur’s high school, Fatih College, is part of a prospering Islamic community associated with Fetullah Gulen, a 62-year-old religious leader who lives in Pennsylvania. In addition to hundreds of schools in Turkey, the Balkans and Central Asia, the loose-knit brotherhood runs a television channel, a radio station, an advertising agency, a daily newspaper and a bank, all pro-Islamic and all centered in Istanbul.

Though little known in the United States, for many years Mr. Gulen was an unofficial ambassador for Turkey who promoted a moderate brand of Islam. He preached tolerance, meeting with Pope John Paul II and other religious and political leaders, among them Turkey’s prime ministers and presidents.

But this month, after a yearlong inquiry, a state security court issued an arrest warrant for Mr. Gulen. A prosecutor has accused him of inciting his followers to plot the overthrow of Turkey’s secular government, a crime punishable by death. The authorities have not tried to extradite Mr. Gulen, but the warrant sent a chill through his circle of admirers and raised anxieties among liberals who are not associated with his movement.

At the same time, the government has been involved in a highly public dispute over its attempt to fire thousands of civil servants suspected of ties to pro-Islamic or separatist groups. Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit sought the authority for the dismissals through a governmental decree, but the president, Ahmet Necdet Sezer, has twice refused to sign the measure into law. Mr. Sezer argues that the authority can be created only by Parliament. The government agreed today to submit the matter to Parliament in the fall.

The deadlock has led to some calls for the resignation of Mr. Sezer, who took office in May. It has also contributed to the almost continuous tension between hard-line backers of the country’s secular order and people who advocate more tolerance of religious views and free speech.

In a written response to questions from The New York Times, Mr. Gulen recently broke a year of public silence about the accusations against him. He described the charges as fabrications by a “marginal but influential group that wields considerable power in political circles.”

He said he was not seeking to establish an Islamic regime but did support efforts to ensure that the government treated ethnic and ideological differences as a cultural mosaic, not a reason for discrimination.

“Standards of democracy and justice must be elevated to the level of our contemporaries in the West,” said Mr. Gulen, who has been receiving medical care in the United States for the past year and said his health prevented his return to Turkey.

Turkey’s military leaders have long regarded Mr. Gulen as a potential threat to the state. Those fears seemed confirmed a year ago when television stations broadcast excerpts from videocassettes in which he seemed to urge his followers to ”patiently and secretly” infiltrate the government.

Mr. Gulen said his words had been taken out of context, and some altered. He said he had counseled patience to followers faced with corrupt civil servants and administrators intolerant of workers who were practicing Muslims.

“Statements and words were picked with tweezers and montaged to serve the purposes of whoever was behind this,” he said.

| At Fatih school outside Istanbul, the young Mr. Elgin, 16, has no intention of overthrowing the state. His sole goal right now is learning enough physics to compete on the Turkish national academic team. |

Mr. Gulen’s explanations are unlikely to satisfy the secular hard-liners who see themselves as the guardians of modern Turkey, which was founded in 1923 by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. For them, the businesses and schools run by his followers sow the seeds of an Islamic regime.

Some moderate Turks see such Islamic-oriented schools and businesses as an attempt to fill a gap left by government policies and discrimination. A study by the private Turkish Economic and Social Studies Foundation found that these Islamic groups appeal not only to the poor but also to strict Muslims who often feel excluded from the mainstream.

The Gulen-oriented schools teach only government-approved religious instruction, in Turkish and English. Tuition payments are several thousand dollars a year, and students face rigorous academic challenges.

“Strategically speaking, the schools are something that should be supported by the state because you have a Turkish presence in these countries,” said Ozdem Sanberk, director of the Economic and Social Studies Foundation.

At Fatih school outside Istanbul, the young Mr. Elgin, 16, has no intention of overthrowing the state. His sole goal right now is learning enough physics to compete on the Turkish national academic team.

Source: New York Times , August 25, 2000

Tags: Fethullah Gulen | Turkey |