Alevi associations react against halt of mosque-cemevi project

Date posted: May 18, 2015

ARSLAN AYAN / ISTANBUL

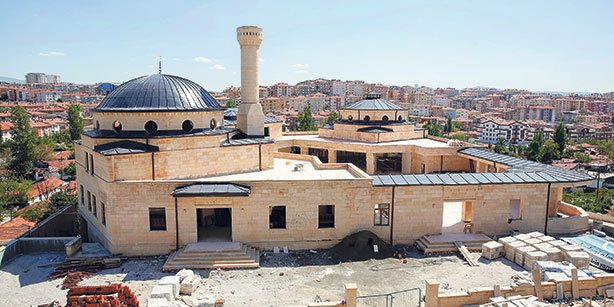

Several Alevi Bektaşi Associations affiliated with the Federation of Alevi Foundations (AVF), which together represent 600 cemevis and 300 local Alevi community associations, have strongly condemned the refusal by Ankara’s Mamak Municipality to grant a certificate of occupancy to Turkey’s first-ever complex housing both a mosque and a cemevi, an Alevi house of worship, on the grounds that it was built with “parallel funds.”

The mosque-cemevi project’s groundbreaking ceremony was held in Ankara in September of last year with the participation of a number of senior Justice and Development Party (AK Party) officials, including Labor and Social Security Minister Faruk Çelik, and Alevi Cem Foundation President İzzettin Doğan, and has been under construction since then. The project, which is being carried out by the Cem Foundation and the Hacı Bektaş Veli Culture, Education, Health and Research Foundation, was first suggested by Fethullah Gülen, a Turkish Islamic scholar whose ideas inspired the Gülen movement, a faith-based civil society initiative. Speaking to the press following the ceremony, Doğan said that when Gülen first suggested the idea of a joint mosque and cemevi, his group welcomed the idea, adding that the project is financed by businesspeople from both the Alevi and Sunni communities.

However, the campus has become the latest victim in the battle launched by the Justice and Development Party (AK Party) government against the Gülen movement. The Mamak Municipality has reportedly refused to grant a certificate of occupancy to the complex on the grounds that it was built with “parallel funds,” referring to businesspeople supportive of the Gülen movement, which is often denigrated by the government as a “parallel structure.”

Turna Alevi Bektaşi Association head and member of the Anadolu Alevi Bektaşi Federation’s executive branch Sevgül Akgün told Sunday’s Zaman that it is upsetting to see that a project like the mosque-cemevi complex has become the subject of political discussion. “If the allegations are true, if the project will be destroyed, this is nothing but a pity. This project is far beyond the political battles, as it is a medicine for the sectarian divides in the region. Alevi-Sunni tension in Turkey is mostly artificial. I mean that it is arbitrarily created and spread among people. These kinds of projects aim to develop the consciousness that Alevis and Sunnis are the subjects of the same God,” Akgün said.

The association head also said that there are plans to launch joint mosque-cemevi projects in five other provinces in addition to the one launched in Ankara, hoping that at least they would not be prevented from going forward with the projects due to political concerns.

“In several provinces and districts, including İstanbul, İzmir, Merzifon, Tokat and Gaziantep, there are plans to launch projects for new complexes housing both a mosque and a cemevi. I currently do not know whether they are going to be launched. No one knows what is going to happen in Turkey. Even the most important projects can be sacrificed for political gain. Innocent people can be accused. And our projects can be defamed with baseless accusations such as ‘parallel funds.’ But we all must understand that these projects are a must for our people. The only way to calm the tension between Alevis and Sunnis is to come up with these kinds of projects. No one would be hurt if a mosque and a cemevi are built next to each other. On the contrary, if they are together, people who visit them come together. The Ankara project should not be sacrificed for political gain,” Akgün added.

Tensions between the Alevi and Sunni communities in Turkey date back to Ottoman times. In 1511, the Ottoman army brutally suppressed a revolt by the Kızılbaş Turkmens of the Alevi faith on Anatolian soil and as many as 40,000 were killed. The Battle of Çaldıran, fought between the Ottoman Empire under Yavuz Sultan Selim and the Safavid Shah Ismail in 1514, resulted in the sultan issuing an edict to kill all the Kızılbaş in the region. During the Turkish republican era, hundreds of Alevis were killed in pogroms, which many now believe were masterminded by groups inside the state, in the cities of Çorum, Yozgat and Kahramanmaraş in the 1970s. Thirty-four Alevi intellectuals were burned to death in 1992 inside the Madımak Hotel in Sivas. In other incidents, such as in İstanbul’s predominantly Alevi Gazi neighborhood in 1995, Alevis were targeted by individuals armed with machine guns.

It was also claimed that another reason for the municipality not to issue the certificate of occupancy was that the mosque within the complex has not been constructed in compliance with the architectural plan approved by the municipality. Speaking to the Sözcü daily last week, Mamak Municipality Vice Mayor Erdoğan Karadağ said the minaret that was built at the rear of the mosque on the right side is not allowed according to the architectural plan. “A tower should have been built instead of a minaret. That is why we did not issue the certificate of occupancy. The minaret is now being destroyed,” Karadağ said.

A certificate of occupancy is a document granted by a municipality to verify a building’s compliance with architectural plans and other laws that confirms the project is suitable for occupancy.

Rıza Akay, a dede, or Alevi spiritual leader, at the Amasya cemevi, voiced his dissatisfaction with Karadağ’s remarks in an interview with Sunday’s Zaman, saying that the reasons put forward by the municipality are nothing but an excuse to stop the project due to political concerns.

“This project was unique in the sense that for the first time in Turkey, a mosque and a cemevi [are being] built together. In both the Alevi and Sunni faiths, tolerance is extremely important. There is no violence and hatred in the Alevi faith. In that sense, maybe in the future, even a synagogue and a church would be added to the complex. But Mamak municipality seems willing to destroy all those efforts to build peace between Alevis and Sunnis. We have to unite against those who want to divide Turkey,” Akay said.

Akay also rejected the claims that the project was funded by businesspeople supportive of the Gülen movement, saying that this project is much bigger than a group of businessmen.

“This complex has been funded by many businessmen from both the Alevi and Sunni communities in order to promote peace. The baseless claims are nothing but attempts to denigrate the project,” Akay said.

The project, which is the first of its kind in modern Turkish history, was expected to be completed in a year and opened during the holy month of Alevis according to the Islamic lunar calendar. The complex was planned to include a conference hall for 350 people, a reading hall for children from disadvantaged families, lounges and guest rooms in addition to a soup kitchen which would be able to accommodate 350 people. There would also be rooms allocated for imams and Alevi religious leaders, called dedes and zakirs, to rest in. Both Sunnis and Alevis would be able to receive funeral services, including the washing of the deceased in accordance with Islamic rules. It would also have a mortuary serving both Alevis and Sunnis.

Turna Alevi Bektaşi Association head and member of the Anadolu Alevi Bektaşi Federation’s executive branch Sevgül Akgün. (Photo: Sunday’s Zaman)

Source: Today's Zaman , May 16, 2015

Tags: Alevi issue | Peacebuilding | Turkey |