Turkish families cope with aftermath of failed coup

Date posted: December 16, 2016

Nick Ashdown

ANKARA, Turkey — “We keep ourselves hidden,” said 22-year-old Ceren,* a recent university graduate. “Right now we’re speaking English, so it’s OK, but normally when we’re speaking to each other, we try to keep our voices low in case someone hears and causes trouble.”

She’s sitting in an outdoor terrace in a mall in central Ankara with four of her friends. They don’t want the people around to understand them because they’re the sons and daughters of some of the most hated people in the country.

Their fathers are generals who have been arrested and accused of involvement in the July 15 failed military coup. They all insist their dads had nothing to do with the deadly coup attempt, which left 272 dead.

Recep, a 20-year-old university student discharged from the Naval War Academy, said he was with his dad at the movies when the coup started.

“They called my father, they said the government was [fallen] and they declared martial law, so he should go back to his office for further information and orders,” he said. “My father went to his units to secure them, not to join the coup. … Orders came, and he knew they weren’t coming from the chief of staff, so he never executed them.”

Ceren was at home watching TV with her dad when news came on about the putsch attempt.

“They said that some soldiers closed the bridge. Everyone at first thought it was a bomb threat. My father was like, ‘If it’s a bomb threat, then why are soldiers there?’ Then he started calling about what’s going on,” she said.

“My father always told me that coups are a bad thing, and now we’re accused of doing one,” said Ece, 22.

The five of them have had their lives turned upside down since July 15, as their fathers have been proclaimed public enemies and their entire families scapegoated.

“They gave 30, 40 years to this country and they’re [being] called terrorists, so it’s really hard,” Ece said. “We are 22 years old and can understand things, but I have a younger brother and he’s 15. Imagine that.”

“They’re calling our fathers traitors,” Recep said, as he showed a news story calling his dad a bastard.

“Even our fathers’ friends keep calling us and saying, ‘We’re ashamed, we wouldn’t expect this from you,’” Ceren said.

Ece said that because of constant uncritical media reports from the largely pro-government media, even family members aren’t sure what to believe.

“When [my uncle] sees news about my father, he’s like, ‘Is it true, did you hear about that?’”

They said their dads were beaten and denied food and water for three days when they were taken into custody. Media reports showed images of arrested officers with obvious injuries, and Amnesty International documented several cases of serious torture.

“A father has the role of being the protector and provider for a family, and you see [him] there being slapped,” Ceren said. “They were stripped, they were tied up, they were waiting in a room with lights on all the time.”

With their fathers in jail and their mothers often devastated, many children of those in custody have been forced to hold their families together.

“All of the older children in this situation have the job of being the [head] of the family because mothers can sometimes have meltdowns. But if we melt down with them, it won’t make anything better, so we have to be the ones to be strong and obviously [earn] money,” said Ceren.

Their fathers’ and mothers’ bank accounts have been frozen, their fathers’ salaries cut, their health insurance canceled and they’ve been kicked out of their military housing.

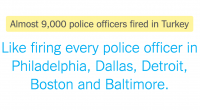

The government blames the coup on Fethullah Gulen, the leader of a global Islamic movement that reportedly had tens of thousands of followers in the Turkish bureaucracy and military. Since July 15, the government has fired or suspended upward of 125,000 people in a colossal purge, but many thousands of them have no clear links to Gulen or the coup.

The generals’ children said their families are followers of the founder of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, an ardent secularist suspicious of Islamic groups.

“We were raised Ataturkcu [Ataturkist],” Ece said.

They believe the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), which has Islamist roots, is targeting secularists.

“They’re trying to erase what Ataturk has said, what he has done, what he has taught us,” Ceren said. “The era of secular people has ended. Now it’s the era of this government.”

The Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) has traditionally been a bastion of Kemalism, the intensely secular ideology of Ataturk’s followers.

Lars Haugom, a visiting scholar at the Norwegian Institute for Defense Studies in Oslo and an expert on the TSK, believes the coup was planned by a mix of factions within the military, not just Gulenists.

“It’s probably correct that the Gulenist officers were kind of the driving force, but I believe there were a lot of officers who were discontented, both with their government and with their own military leadership,” he said.

Of 358 generals and admirals in the TSK, 178 were detained after the coup and 149 were dishonorably discharged. Haugom believes many of them may have been targeted for their perceived lack of loyalty to the AKP.

“I think that those [who were] dishonorably discharged after the coup, they were probably all the top leaders who were not trusted for one reason or another,” he said. “I think they’ve discharged a lot more people than were actually involved with the coup.”

Haugom said some of the purged officers haven’t been proven guilty for their alleged crimes.

“You’re normally innocent until proven guilty. In this case, I think it’s the other way around,” he said.

He also said the purges and restructuring of the TSK seem more about politicization than civilian oversight.

“Even if you get more civilian control, it’s not more democratic,” he said. “It seems to be about party control, with [Turkish President Recep Tayyip] Erdogan and the AKP seeking to strengthen their control of the military.”

Ceren fears there’s little left to stop the authoritarian Erdogan now.

“No one can say no to him,” she said. “This is his kingdom now.”

*The arrested officers’ children’s real names are not used in this story.

Nick Ashdown is a Canadian freelance journalist who has been based in Istanbul for three years.

Source: Al Monitor , December 16, 2016

Tags: Human rights | Military coups in Turkey | Turkey |